Understanding TJC's Worksite Analysis for Healthcare Workplace Violence Prevention

Effective January 1, 2022, The Joint Commission (TJC) rolled out new and revised standards for workplace violence prevention in healthcare. These new standards reflect a major change in the approach to workplace violence in healthcare by emphasizing PREVENTIVE measures along with its previously published RESPONSE protocols.

One of the foundational requirements contained in the new and revised standards is that each accredited organization must conduct an “Annual Worksite Analysis” with a specific focus toward prevention of workplace violence.

In our comprehensive review of the new and revised standards, along with several discussions we’ve had with a variety of healthcare leaders, we’ve concluded that the work site analysis is a critical component of these new standards. It’s important for organizations to begin preparations now for future Joint Commission Surveys and the Worksite Analysis Framework is the best way to make those preparations.

Meaningful or Moot?

In discussing his theory of program analysis and management, one of my grad school professors often stated, “I can’t measure something I can’t count, and I can't evaluate something I can't measure.”

While I understood the basic wisdom behind my business professor’s statement, when applying it to real-world business issues, I realized it was also vital to understand what I was ACTUALLY counting and what I was ACTUALLY measuring.

The real challenge for any organization conducting a true self-analysis is to determine the right performance metrics: What are we counting, what are we evaluating, and how does that connect and advance the mission? Essentially, are we asking the right questions?

We must have metrics that are relevant and meaningful, otherwise our analysis will be moot.

Don Robinson

In the sections below we’ll discuss some best practices and actions that healthcare organizations should take now to be compliant with the new standards and initiate a more ongoing and active approach to reducing violence in their workplace.

Do you have a policy or program that focuses on PREVENTION?

Workplace violence prevention and response efforts present unique challenges in the healthcare arena. Typical interventions used in other business sectors (e.g., refusing service to an aggressive or threatening customer) are simply not an option.

In most cases, hospitals and healthcare organizations cannot refuse to care for a disruptive or even violent or agitated patient. This unique mission requirement makes having a robust workplace violence prevention program --with a strong focus on both prevention and mitigation—critically important.

If yours is like most organizations, you do have a written workplace violence prevention policy. But the key question here is: do you ACTUALLY have a functioning program based on this policy and one that conducts ongoing, active measures to prevent, detect, identify, mitigate, and/or respond to incidents of workplace violence?

In our work with healthcare organizations, we’ve had the opportunity to participate as active members and advisors on a wide variety of workplace violence prevention committees. As such, we’ve had exposure to a wide range of committee models addressing the issue of workplace violence. We’ve found that many of these committees merely become a vehicle for reporting statistical or demographic information. A typical meeting can often sound something like this, “during the last month we had 27 documented assaults against staff, 32 calls for service for the local Police Department, and we confiscated 42 weapons. OK, next item on the agenda.” In this type of cursory format, little work is done to address root causes or come up with actual solutions to address future incidents related to workplace violence. Such meetings may have satisfied previous regulatory or accreditation requirements, but that will no longer have sufficient reach to maintain compliance under the new TJC standards. In this new world, healthcare organizations must now have a documented program that addresses prevention of future incidents.

Are you prepared to take a multi-disciplinary approach to Worksite Analysis?

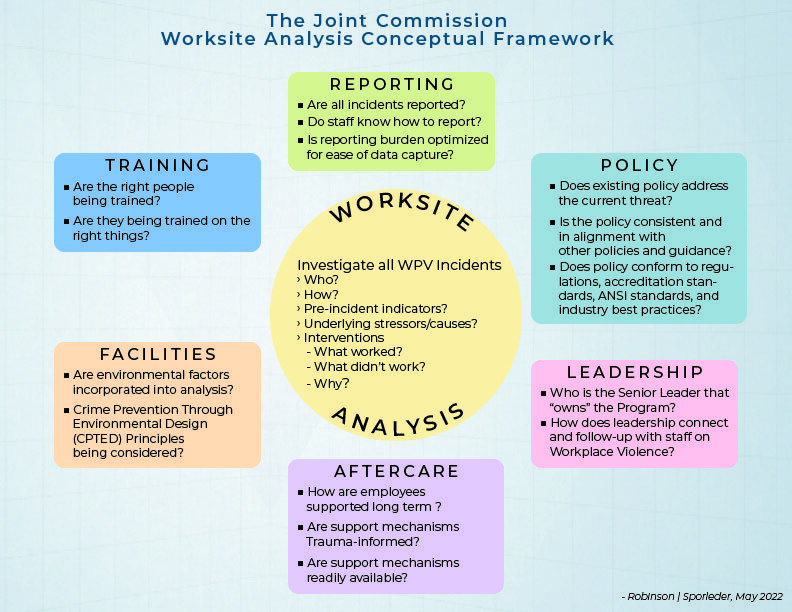

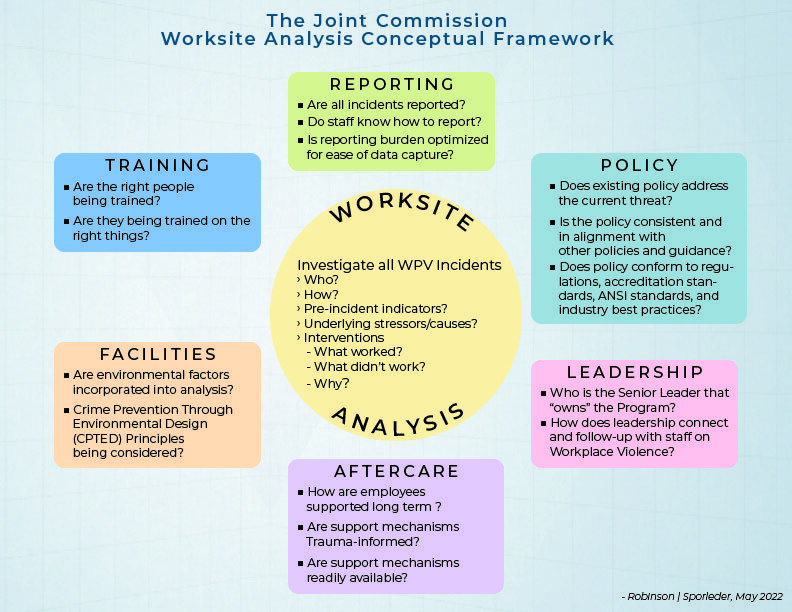

The first key element of the new TJC standards is a requirement to conduct a PROACTIVE analysis of workplace violence events. That means acting in anticipation of future problems, needs, or changes.

Under the new Joint Commission standards, any worksite analysis must seek to “identify, address, and mitigate gaps and trends in workplace violence incidents within an organization.”

For example, if an ongoing analysis shows a spike in workplace violence incidents in one unit of a healthcare organization, what conclusions might be drawn from that?

- Could the increase in violent incidents be directly attributed to the increased boarding of psychiatric patients on specific medical/surgical units while awaiting appropriate beds in a behavioral health unit?

- Or are the bulk of workplace violence incidents during a specific period stemming from a particular patient who may be problematic while awaiting placement in a different facility?

A true TJC compliant worksite analysis will attempt to look at ALL factors surrounding a specific incident or a noted spike in violence in a specific unit, but through a lens of prevention to identify pre-incident indicators as well as evaluate the efficacy of any interventions. Other multi-disciplinary factors might also be considered.

For example, with regard to the facility:

- Are there principles of Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) that can/should be employed to increase staff safety and reduce the incidence of workplace violence?

Broad spectrum, multi-disciplinary questions like these should be considered when conducting a worksite analysis under the new standards. Inherent in the worksite analysis is the requirement to conduct a full investigation of all workplace violence incidents. While some might argue that there is little to investigate beyond the individuals involved and what happened, conducting a full investigation that will inform workplace violence PREVENTION efforts, considers several other factors.

Here’s a sampling of questions that might be included.

- What is the known background of the person that assaulted the staff member?

- Were there any-pre incident indicators prior to the assault?

- What interventions were employed to address the workplace violence incident?

- Were those interventions effective?

- Were there any other factors that either aggravated or mitigated the act of workplace violence? (Factors such as facility design, staffing, other interaction with staff, family members, or visitors.)

A true investigation takes a multi-disciplined approach focused on the widest variety of factors possible as a means of developing an all-encompassing and holistic image of the events leading up to the incident, the incident itself, and the organization's response to the incident.

Will your plan address underreporting, frustrating documentation and need for aftercare?

A persistent problem in assessing an organization's true threat from workplace violence is the lack of information. Multiple studies indicate that workplace violence in healthcare is underreported by a factor of at least 70% or greater.

Informal climate surveys reviewed by our team overwhelmingly confirmed that workplace violence in healthcare is vastly underreported. Many reasons are cited by staff, but a common theme that emerges from all the responses is a lack of confidence that any substantive organizational change will actually take place.

Staff have also reported frustration with existing reporting mechanisms, claiming they are not user friendly and involve a heavy time commitment. Speaking from personal experience, it is not surprising that a nurse who’s just completed a 12-hour shift after being assaulted by a patient would not be motivated to remain at work for an extra 30-45 minutes to fill out an incident report (the norm of which typically requires the completion of a clumsy security or risk management reporting application). Healthcare employers must do better to remove the barriers to timely and accurate reporting.

We’ve had the opportunity to review several common risk management and security reporting applications used in the healthcare sector and the challenge is that they are typically designed with the interest of the end user in mind.

For example:

- a well-known risk management reporting application that’s designed to aid risk managers, requests and collects information in a format that’s useful to risk managers. Now, there's nothing wrong with that except it places an added burden on the victimized employee to enter administrative and demographic data that’s useful to risk managers. A recently victimized employee should only be responsible for telling the story of what happened and not searching for the correct incident codes in an awkward data collection application.

The climate surveys of bedside clinical staff conducted by our team and others show a solid trend and an entrenched mindset within the nursing career field that verbal, and even physical abuse, is just simply “part of the job.”

We must change the narrative that some abuse is simply "part of the job" in healthcare. While progress is being made, it’s coming far too slowly.

To that end, The Joint Commission standards also call on healthcare organizations to develop programs and processes for follow up and support to victims and witnesses affected by workplace violence, which includes trauma-informed psychological aftercare. Simply providing a point of contact to a contracted Employee Assistance Program (EAP) provider that may or may not be able to connect the victim employee with services in a timely manner is not enough. Healthcare has recognized this gap and recently there have been several programs developed to meet this critical need. One such program, the RISE program developed by Johns Hopkins Medical Center, involves the use of trained peer counselors to provide near-real-time support to those employees impacted by workplace violence incidents. This program has proven to be highly successful in addressing the concerns of victimized employees and is a positive development in helping to turn the tide in this often-beleaguered career field.

Is your organization willing to see this as an ongoing analysis of workplace violence at the operational level?

Finally, it would be a mistake to view the new requirement for an annual worksite analysis as simply another “annual requirement” that must be met.

The analysis must take a long-term prevention-centric view in detecting, identifying, and mitigating trends, gaps, and other systemic vulnerabilities. However, it must also be responsive in making necessary mid-course corrections during the year to address emergent threats, gaps, vulnerabilities, and needs. We recommend monthly workplace violence prevention committee meetings with a portion of each agenda dedicated to a discussion of past incidents and remediation efforts, as well as ongoing prescriptive analysis of data gathered to date.

We also recommend periodic consultation with external subject matter experts. Every two-to-three years these external subject matter experts should conduct a thorough review of existing policies and procedures, crisis management and emergency response plans, as well as reviewing all prior annual worksite analysis documentation. This review will ensure compliance with accreditation standards, federal, state, and local regulations (as applicable), as well as conformance to current industry best practices.

Here's an example of what a TJC compliant Worksite Analysis Framework might look like:

For additional information and resources, download our Checklist To Meet the New 2022 TJC WPV Standards.

About the Authors

Don Robinson

For 23 years, Don worked for the FBI – specializing in counterterrorism, organized crime and narcotics investigations, and serving as a regional program coordinator for FBI Domestic Terrorism, Civil Rights and Organized Crime programs. After retiring, Don began a second career in behavioral health where he established one of the first Behavioral Health Crisis Centers and served as the Manager of Behavioral Health Crisis Intervention Services at a 296-bed community hospital.

Don is an experienced Crisis/Hostage Negotiator, a Certified Threat Manager®, and a certified law enforcement instructor. He has trained foreign and domestic governmental agencies, law enforcement/security entities, educational institutions, healthcare organizations, social service agencies and community non-profit organizations. He is an active member of ASIS International and the International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety (IAHSS).

James Sporleder

James Sporleder is a national-level expert in workplace violence prevention and empathy-centered approaches to reducing interpersonal violence and other forms of harmful behavior. With more than 30 years’ experience, he helps organizations recognize and respond to behaviors of concern before they escalate, integrating trauma-informed practices and early-recognition strategies that align with leading national standards.

James currently serves on the ASIS International Technical Committee revising the American National Standard on Workplace Violence Prevention and Intervention and is a contributing content author and subject matter expert with Atana. His programs and expertise support safer, more connected, and prevention-focused workplaces across all industries.